Oil and water: Lessons from the Deepwater Horizon BP oil spill

For many, April brings the hope of rebirth – new beginnings, springtime, Earth Day. For me, however, April always reminds me of the hopeless feeling in spring 2010, as we all watched – month after month – as huge quantities of oil spewed into the Gulf of Mexico. This Sunday’s anniversary presents an important chance to review what we have learned, and not yet learned, from this tragedy, and what those lessons might mean for the future of the Gulf.

The U.S. was simply not prepared for a challenge of this magnitude. Despite previous spills like Ixtoc (1979), Exxon Valdez (1989), Montara/Timor Sea (2009) and many more, the protection and response systems were not in place to address a large-scale oil catastrophe. It took three months before the well could be sealed. During that time, more than 200 million gallons of crude oil gushed into the Gulf, carried by the currents, creating a widening area of oil pollution.

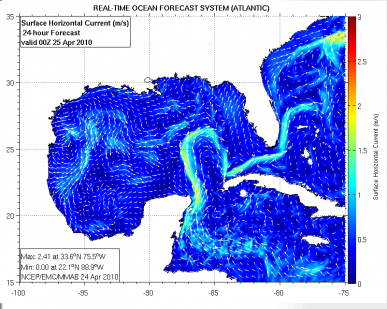

We came very close to causing an international incident. It was only through the vagaries of the Gulf Loop Current that the best beaches and most valuable coral reefs, seagrass beds and mangrove swamps downcurrent in Florida and Cuba were not slimed with U.S. oil. As it was, oil-based fisheries closures in U.S. waters extended to more than 150 miles of the edge of Cuba’s Exclusive Economic Zone. No one knows how much oil entered Cuban waters. It remains a great irony that we U.S. citizens have been so afraid of Cuban oil development, when U.S.-derived oil very nearly destroyed essential shared resources in Cuban waters in 2010!

Gulf Loop Current conformation on April 25, 2010; Credit: NOAA

Oiled sea birds, sea turtles and marine mammals received abundant press, all around the world. Oil-polluted beaches and marshes were on everyone’s front page. Unfortunately, the natural resources certain to be most damaged received short shrift, because they were both poorly recognized and monitored.

Out-of-sight, and so out-of-mind

A dispassionate scientific review makes clear that the biggest environmental impacts were felt by small and sensitive early life stages, and creatures of the deep. Especially vulnerable elements included tiny floating larvae of local seafood species (including shrimp, crabs, and many shellfish species, spawned offshore and drifting back nearshore where their nurseries occur), and similarly small larvae of species that use the Loop Current as a highway in the sea for transport of their young.

The plight of ancient deepwater corals and other bottom dwellers bathed in erupted oil, and then also rained upon by oil remnants sinking back from the surface, was also largely ignored. Some of those corals take thousands of years to grow.

In addition, oil suffocated large areas of the extraordinarily dense layers of life of the middle zone of the sea – where light does not penetrate, but now widely recognized as one of the sea’s great natural resources. This so-called “deep scattering layer” of life holds much of the ocean’s living mass, and serves as forage for squids and other residents as well as deep-diving tunas, billfishes and marine mammals.

The big impact on the large population of sperm whales in the northern Gulf was not from direct oiling, but from impacts through their food, occurring in the unseen depths. None of these deep resources are well-studied, and none received baseline monitoring beforehand.

In my view, few of the most damaged natural resources are well-known enough to calculate the natural resource damages much less the compensation payments they deserve. It will probably take many years before scientists can look back and guess the degree to which the future populations were damaged by oil pollution exposure.

I believe that it will turn out that use of dispersants on the bottom should never have been approved. Those materials were not only incrementally toxic, but they also greatly expanded the zone of sub-surface toxic exposure, and the complexity of transport-and-fate relationships for oil-derived pollutants, not to mention making recovery on the surface less certain. That such a decision would have to be made in the heat of response clearly illustrates the degree to which those response systems were inadequately prepared.

The fact that we were a mere razor’s edge away from much worse impacts – including those downcurrent in Cuba and Florida – clearly illustrates the folly in our nation’s unwillingness to engage with Cuba in managing shared resources.

If our “oil history” reveals one thing it is that spills and even gushers will occur again, and that we must be prepared. Perhaps the best single result of Deepwater Horizon – from the ocean perspective – it that we are now talking and planning for such responses. Many other good things are also happening in the Gulf now – sustainable commercial fisheries for red snapper and other reef fishes, the “Gulf Wild” safe seafood program, new momentum to rebuild the Mississippi Delta, and others.

At the end of the day, much more needs to be done for nature and for the people of the Gulf so that this mighty ecosystem can be safe for the future.

I have a friend who works in the aviation training field. He once told me that almost every safety feature you see in any aircraft today was the direct result of a catastrophic failure brought on by the inability to see said failure before it became critical, or a complete lack of understanding/acceptance of what risks actually existed.

This made complete sense to me, and the more I thought about the more I could see this is how we apply ourselves in every area of mechanical and technical development.

Rick Maher

August 16, 2018 at 9:59 am